Data mesh principles and logical architecture

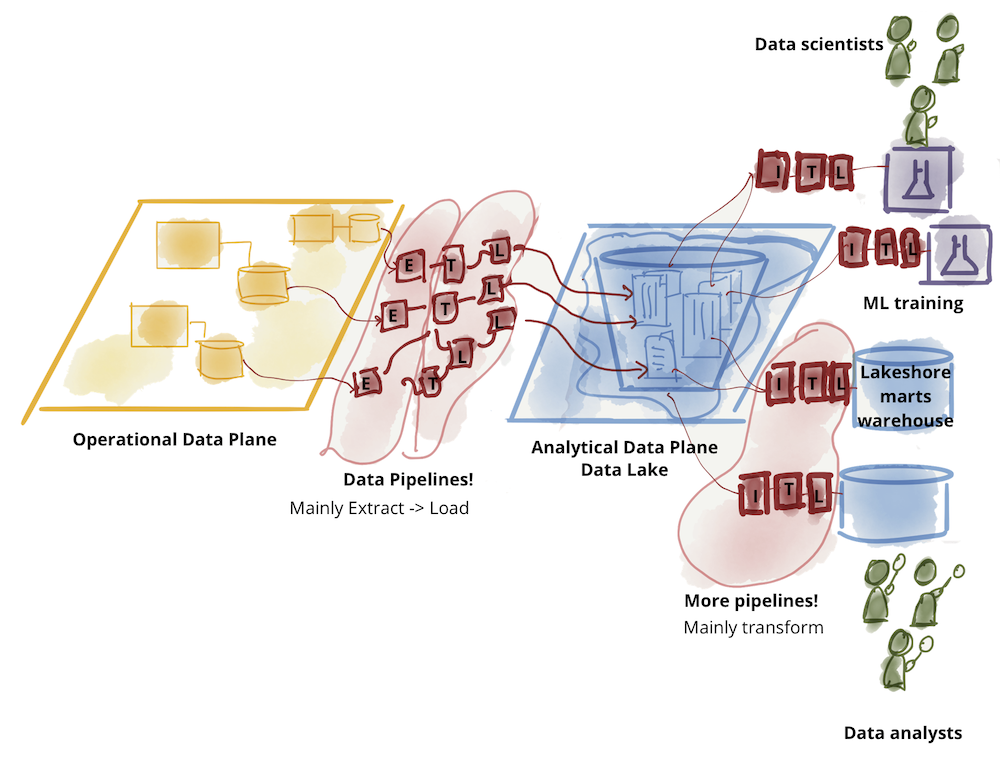

Analytical data plane itself has diverged into two main architectures and technology stacks: data lake and data warehouse; with data lake supporting data science access patterns, and data warehouse supporting analytical and business intelligence reporting access patterns. For this conversation, I put aside the dance between the two technology stacks: data warehouse attempting to onboard data science workflows and data lake attempting to serve data analysts and business intelligence. The original writeup on data mesh explores the challenges of the existing analytical data plane architecture.

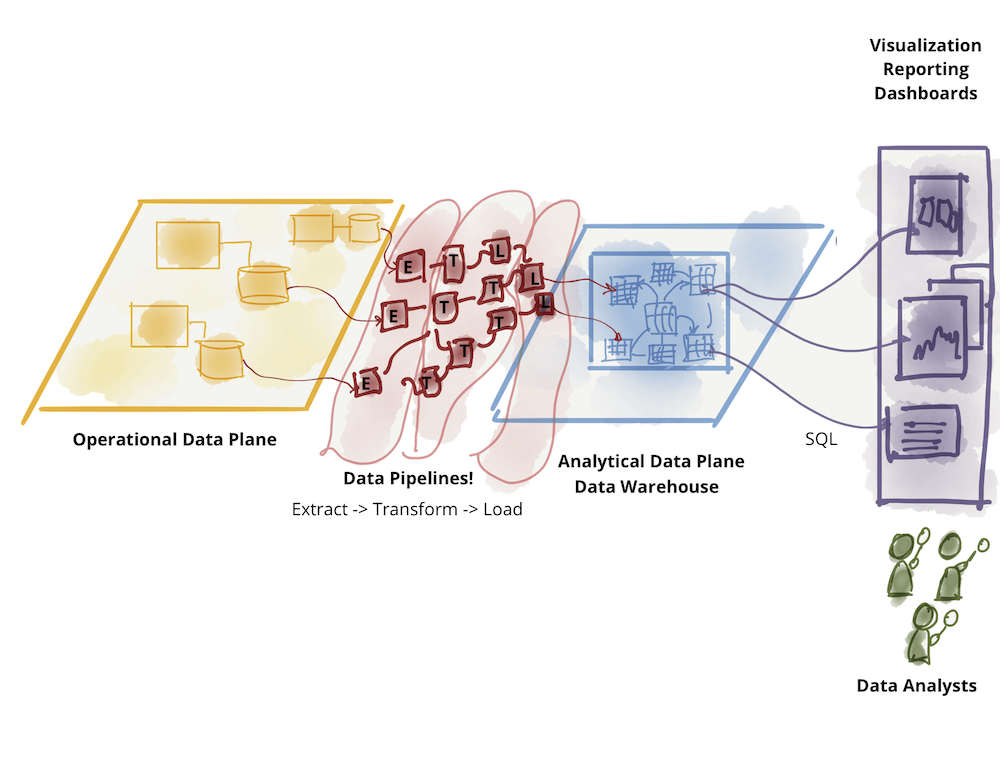

Further divide of analytical data-warehouse

Further divide of analytical data-warehouse Further divide of analytical data-lake

Further divide of analytical data-lake

Interview with Jon Corbett

Modern computing frameworks (not just programming, but computing technologies in general) are often focused on efficiencies, logics, and choices that are typically not as valued in Indigenous cultures. Similarly, activities the computer does have evolved from notions of time and behaviors that don’t always reflect Indigenous concepts of “natural” orders. So an Indigenous computing framework puts into practice Indigenous concepts and knowledge. It may not necessarily change or alter the way the computer handles instructions, but it changes the philosophies used in construction and development of software and hardware such as my Cree programming language; and a syllabic keyboard that does not conform to the horizontal rowed keyboards that are ubiquitous to modern computing practices.

Additionally, this framework introduces axiological (i.e. ethical and spiritual) considerations into the computer’s systemic process, something that does not exist (as far as I know) in the traditional development of computing materials. There does exist some research on “spirituality AND technology” but nothing to my knowledge that treats technology as an integral component of a human’s spiritual being or existence. (Science fiction and cyborgism dabble in these kinds of things, but what I propose is kind of different? I think? lol)

There are a number of concepts that as a programmer I have come to just accept. Things like “data types”, “variables”, “looping”, “conditionals”, and “linear/sequential instructions”. Simply translating these into Cree is not that simple because some of these concepts don’t necessarily exist. Take for example English as a collection of 26 letters that form an alphabet, and is often taught as “ABC’s”. We are taught to read and learn these letters in a left to right sequential fashion, and is very much an algorithmic methodology. But Cree is often taught in a very heuristic and organic way, and is difficult to describe in an “alphabetic ordering”, this system of organization won’t always work.

So Cree is more of a lateral/parallel thinking form of language (as opposed to serial/sequential per se), so creating a language that relies on a linear (ie line by line process) is one of those “accidentals”. In designing a programming language for Cree, my challenge is to figure out answers to:

Is this process necessary? i.e. Must it exist in a linear system? Do I actually need “lines of code”?

Can lines of code be grouped and collected and executed in any order and still produce similar results to a strictly linear process?

The Cree Star Chart of syllabics is a 2D representation of the language, so can the new programming language also be represented in a 2D format? And how would that work? Is a visual object language better suited?

Many [English] programming languages rely on extended symbols and punctuation like quotation marks, semi-colons, braces/brackets, etc.. to mark code for function – in Cree written language there is no punctuation except a period. So is introducing punctuation and symbols that are not part of the language acceptable for purposes of “programming” or is it a form of colonial homogenization?

How the PostgreSQL optimizer works and speeds up queries

Implicit vs. explicit joins in PostgreSQL

Many people keep asking about explicit versus implicit joins. Basically, both variants are the same. Let’s check out two queries and see what we are actually talking about in the context of PostgreSQL:

SELECT * FROM a, b WHERE a.id = b.id;vs.

SELECT * FROM a JOIN b ON a.id = b.id;Both queries are identical and the planner will treat them the same way as for most commonly seen queries. Mind that the explicit joins work with and without parenthesis. However, there is one parameter that is of great importance here:

demo=# SHOW join_collapse_limit; join_collapse_limit --------------------- 8 (1 row)The

join_collapse_limitcontrols how many explicit joins are planned implicitly. In other words, an implicit join is just like an explicit join, but only up to a certain number of joins controlled by this parameter.For the sake of simplicity, we can assume that it makes no difference for 95% of all queries and for most customers.

EXISTS and anti-joins

There is also a quite common thing you will see everywhere in the code within SQL EXISTS. Here’s an example:

demo=# explain SELECT * FROM a WHERE NOT EXISTS (SELECT 1 FROM b WHERE a.x = b.x AND b.x = 42); QUERY PLAN ------------------------------------------------------------------- Hash Anti Join (cost=4.46..2709.95 rows=100000 width=8) Hash Cond: (a.x = b.x) -> Seq Scan on a (cost=0.00..1443.00 rows=100000 width=8) -> Hash (cost=4.44..4.44 rows=1 width=4) -> Index Only Scan using b_x on b (cost=0.42..4.44 rows=1 width=4) Index Cond: (x = 42) (6 rows)This might not look like a big deal, but consider the alternatives: What PostgreSQL does here is to create a “hash anti-join”. This is way more efficient than some sort of nested loop. In short: The nested loop is replaced with a join which can yield significant performance gains.

My sign of a good graphical interface

Here is a thesis I have about really good graphical interfaces, especially in the context of text editors:

In a good graphical interface, you not only can use the mouse, you want to.

There are a good number of graphical interfaces that are ordinary and decent and good enough. They make effective use of the mouse and graphics, they’re nice, and they by and large fail to fill me with any particular actual enthusiasm for those graphical features. They’re just sort of there, in an ordinary and perfectly acceptable way.

Modern CI is too complex and misdirected

I posit that a sufficiently complex CI system becomes indistinguishable from a build system. I challenge you: try to convince me or yourself that GitHub Actions, GitLab CI, and other CI systems aren’t build systems. The basic primitives are all there. GitHub Actions Workflows comprised of jobs comprised of steps are little different from say Makefiles comprised of rules comprised of commands to execute for that rule, with dependencies gluing everything together. The main difference is the form factor and the execution model (build systems are traditionally local and single machine but CI systems are remote/distributed).

Then we have a similar conjecture: a sufficiently complex build system becomes indistinguishable from a CI system. Earlier I said that CI systems are remote code execution as a service. While build systems are historically things that run locally (and therefore not a service), modern build systems like Bazel (or Buck or Gradle) are completely different animals. For example, Bazel has remote execution and remote caching as built-in features. Hey — those are built-in features of modern CI systems too! So here’s a thought experiment: if I define a build system in Bazel and then define a server-side Git push hook so the remote server triggers Bazel to build, run tests, and post the results somewhere, is that a CI system? I think it is! A crude one. But I think that qualifies as a CI system.

If you squint hard enough, sufficiently complex CI systems and sufficiently complex build systems start to look like the same thing to me. At a very high level, both are providing a pool of servers offering general compute/execute functionality with specialized features in the domain of building/shipping software, like inter-task artifact exchange, caching, dependencies, and a frontend language to define how everything works.

(If you squint really hard you can start to see a value proposition of Kubernetes for even more general compute scheduling, but I’m not going to go that far in this post because it is a much harder point to make and I don’t necessarily believe in it myself. But I thought I’d mention it as an interesting thought experiment. But an easier leap to make is to throw batch job execution (as is often found in data warehouses) in with build and CI systems as belonging in the same bucket: batch job execution also tends to have dependencies, exchange of artifacts between jobs, and I think can strongly resemble a CI system and therefore a build system.)