Sorting Lego parts, it should be easy

Sorting Lego parts can be an interesting activity when you enjoy overthinking[1].

When I dismantle a large model, I put the parts in boxes to make them easier to find back later. It means deciding how to sort the parts into different boxes.

The usual situation is the one depicted on the above picture: there are a few self-evident groups, and some other parts that don’t fit in these groups. Some parts could be put in the groups if I somewhat relax the criteria I established in my head, and others don’t match at all.

Is pink a kind of red?

In the picture, I created groups for the colors with the most parts. I can put the pink parts in the red parts box, if I decide that pink is redish enough that I’ll remember to look for them there, or I can decide that pink is its own color and deserve better than to be mixed with the reds.

But then what should I do with the remaining parts, including or not the pink ones?

I could create an “other” box. I could also get a box for each color if I want to apply my “one box per color” rule without an exception.

Considering some of the groups have often much more parts than other, I can decide to split them to have more or less the same number of parts in each group if I can find a good criterion, because much more parts would make finding parts in these groups longer.

On the other hand, there is straightforward solution: a single box for each color. Or even better: a single box for each color and part types.

This way there is no judgement call to be made: the sorting criterium is fully objective.

Except I would have a lot and lots of boxes, which would highly impractical.

The single objective rule approach

The single objective rule approach can be used for lots of things beyond Lego parts.

I understand its appeal: it feels pure and has a kind of intellectual high ground compared to more complex ones that feels messy compared to it.

But, as for the Lego parts case, using it can have drawbacks, but these are softer than the hard hammer of the single rule, so these aspects are often crushed.

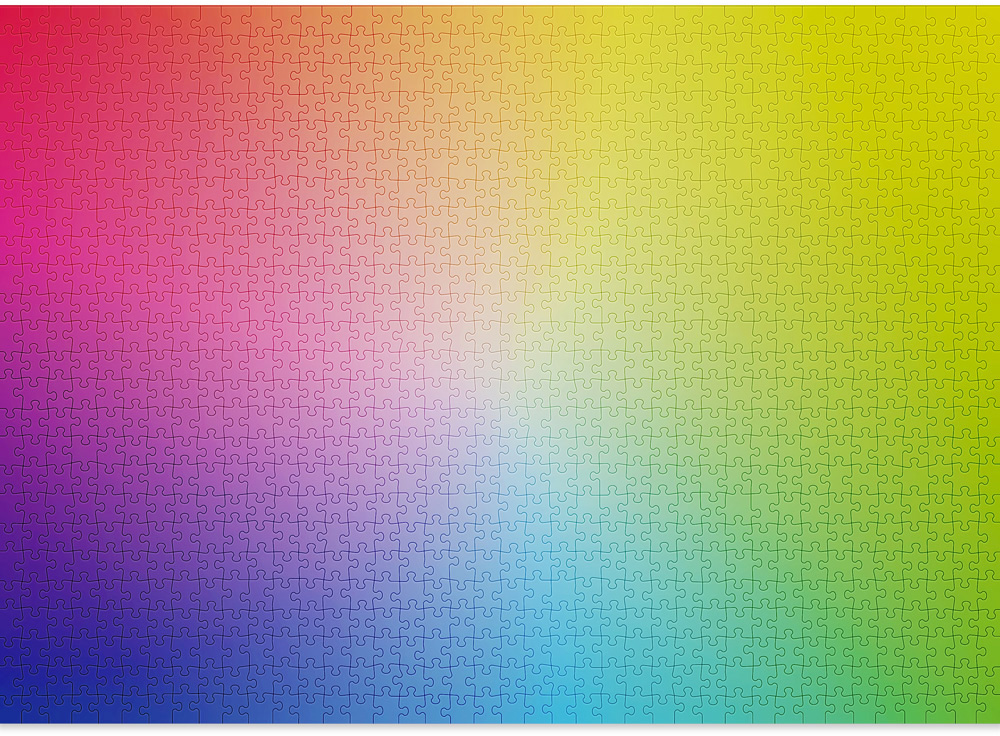

Sorting jigsaw parts looks like sorting Lego parts, only with more messiness because there are less hard facts you can base your sorting on.

Now imagining using the “a single box by type” for this jigsaw:

The single objective rule and software design

One of my personal nemesis about designing software is when people indistinctly apply the single objective rule.

Indistinctly is important, because I don’t mean that this rule isn’t the right choice in some cases, for example this rule can bring consistency, and consistency can be an incredible tool to increase the usability of a tool.

But my gut feeling is that this rule is employed too often, and it’s frustrating because as I’ve mentioned above, it can be difficult to argue against it, especially when not applying it means making things messier.

Arguing for a messier approach with some software people is not a piece of cake.

A common example of overapplying this rule is when people want to miscreate indirections because they decide that one type of code shouldn’t call another type.

I’ve worked on several projects that wanting to isolate the business code from the libraries they used, and it meant that for each API of the library, we had to create some custom code to add a layer of indirection.

Most of the cases, the custom code mimicked the API of the library, because creating “an abstraction” when you have only one example is very difficult, so swapping to another future library would probably mean to change the custom indirection API, which meant changing the business code.

It felt very much like having one box for each jigsaw part.

A coworker shrewder than me suggested that we could generate our decoupling API from the library API, but it would have made the uselessness of the whole thing too obvious.

In some case, it has helped with testing, when we had to use mocks and the related library was mock-hostile. In other cases, it leaded to a more compact API, because it enabled us to remove some methods parameters we didn’t use, until we needed them and had to rework the thing.

Of course, there were exceptions to the rule, for libraries whose API would have been too complex to create indirection for. But the criteria for the exceptions weren’t explicitly written because it would have meant stopping having the single official rule.

I dislike messy things, and I like to have a single rule to follow when it’s appropriate, but sometimes being a bit messy is better than doing work that brings little value except compliance with a rule, or worse, actively makes things worse.

I don’t want to write another indirection above a logging library.

So, please, when you feel the appeal to establish a single objective rule, try to resist it and think of the drawbacks. We should strive for simplicity, but I think software design should be something else that picking a few absolute rules and applying them relentlessly.