Publié en 1996, Measuring and Managing Performance in Organizations s’intéresse particulièrement à l’activité de développement logiciel.

Même s’il a plus de vingt ans, cet ouvrage reste parfaitement d’actualité. Il le restera sans doute longtemps car sa démonstration va à l’encontre du discours ambiant et demanderait aux organisations de revoir leur méthode de management. Une telle évolution a peu de chances d’arriver, comme en témoignent les discussions actuelles sur l’agile en général et le no estimate.

Dans ce livre, Robert D. Austin propose un modèle qui permet de répondre aux cas limites des approches généralement appliquées.

L’auteur appuie son argumentation sur des références abondantes, principalement du côté des économistes car dans une logique économiste, les situations qu’il décrit ne sont pas des aberrations mais correspondent à des comportement rationnels.

Mesurer les activités

Robert D. Austin définit une “dimension critique” comme une caractéristique déterminante pour le résultat d’une activité. Par exemple le nombre d’objets d’un certain type produit par une personne.

Il propose de classer les activités en trois catégories en fonction du niveau de mesure de ces dimensions critiques :

-

Supervision complète : quand l’ensemble des dimensions critiques de l’activité sont mesurées ;

-

Absence de supervision : quand aucune des dimensions critiques de l’activité n’est mesurée ;

-

Supervision partielle : quand seulement une partie des dimensions critiques de l’activité sont mesurées.

La première catégorie correspond à un travail où tout ce qui est important est mesuré, par exemple un processus de fabrication où toutes les caractéristiques de l’objet fabriqué sont mesurées.

La deuxième peut correspondre au cas d’un expert ou d’une experte dont le travail en très difficile à mesurer.

La troisième catégorie correspond à la majorité du développement en informatique de gestion.

Supervision partielle et objectifs

La question centrale du livre est celle de la compatibilité du management de la productivité avec une situation de supervision partielle.

La pensée managériale classique met l’accent sur l’importance de donner des objectifs quantifiés pour motiver les personnes dans leur travail.

En cas de supervision partielle, les objectifs quantifiés ne couvrent donc qu’une partie des critères qui déterminent le résultat de l’activité, certains des critères n’étant pas mesurés.

Selon les ressources citées par l’auteur, les personnes sont en général motivées par l’idée un travail de qualité car elles en tirent de la satisfaction.

Dans une situation de supervision partielle, faire un travail de qualité signifie effectuer des efforts qui ne sont pas mesurés, et donc ne sont pas couverts par les objectifs.

Ainsi, à niveau d’effort équivalent, la personne doit choisir entre :

-

se concentrer sur la qualité du travail, sans que l’atteinte des objectifs soit une fin en soi ;

-

se concentrer sur les aspects mesurés pour atteindre un niveau d’objectif plus élevé. Cela diminue le résultat du travail mais d’une manière qui n’est pas mesurée par le système.

Au-delà d’un certain niveau d’effort ou d’une certaine pression sur les résultat, il est rationnel pour la personne de basculer vers la deuxième posture : à un moment, mieux vaut des revenus supplémentaire que faire du bon travail.

L’auteur met ainsi en lumière l’opposition entre le discours sur l’autonomie des personnes et le fait de surveiller leur activité : demander aux personnes de s’impliquer dans leur travail et de faire les meilleurs choix pour leur organisation n’est pas compatible avec une supervision partielle, car cela créé une situation où l’intérêt de la personne est opposée avec celle de l’organisation.

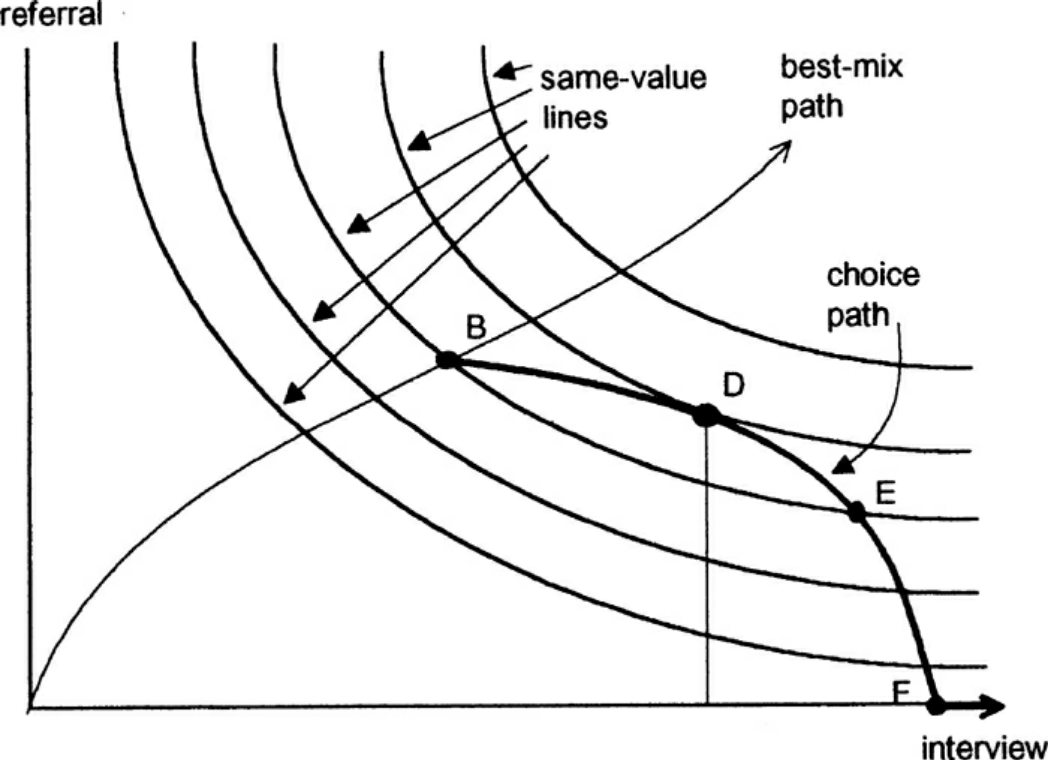

En cas de supervision partielle, l’auteur conseille donc de ne pas utiliser le management par objectif mais plutôt d’utiliser le management délégatif (“delegatory management”) qui repose sur la confiance et la motivation interne.

La supervision totale

Dans une situation de supervision totale, le système est entièrement connu et le pilotage par objectifs chiffrés est adapté.

C’est le modèle prépondérant dans les théories du management actuel, celui où les personnes peuvent être controlées comme des machines et qui correspond à une certaine vision du fonctionnement d’une usine.

La facilité de manager ce modèle le rend très attractif, à tel point qu’en cas de difficulté dans une organisation, la tentation est parfois très forte de réorganiser le travail pour aller vers ce type de fonctionnement.

Par exemple, c’est le cas quand dans une situation de crise un ou une responsable d’équipe veut “reprendre la main” en pilotant directement l’activité des personnes, ou en découpant chaque activité en micro-tâche pour avoir une meilleure vision de l’avancée du travail.

Selon l’auteur, une partie de l’attrait de la standardisation des processus internes aux organisation relève moins de la volonté d’augmenter l’efficacité que de celle de pouvoir rendre mesurables l’activité des personnes, et donc d’augmenter la capacité de supervision.

Totale ou partielle ?

Choisir la bonne méthode de management nécessite donc de savoir quel type de supervision s’applique, et donc de savoir si toutes les dimensions critiques sont bien mesurées.

Trois exigences doivent êtes respectées :

-

que les dimensions critiques soient toutes identifiées ;

-

qu’elles soient toutes mesurables ;

-

qu’elles soient toutes mesurées.

Si un seul de ces critères n’est pas rempli, il ne s’agit pas d’une supervision totale.

Selon l’auteur, beaucoup de situations considérées comme de la supervision totale ne le sont pas.

Cela peut avoir de nombreuses causes, comme la difficulté à identifier toutes les dimensions critiques ou la difficulté de mesurer certaines d’entre elles.

Face à l’envie d’appliquer tout de même le management par objectif, il peut être tentant de faire semblant de ne pas savoir que tout n’est pas mesuré, ou de prendre une mesure indirecte pour une mesure directe. L’exemple classique est d’utiliser le nombre de lignes de code comme indicateur de productivité.

Le système devient alors très compliqué à piloter, car l’outil de commande utilisé ne couvre pas l’ensemble des variables existantes.

On peut l’observer quand une organisation modifie en permanence la manière dont les objectifs sont évalués pour essayer de trouver le bon équilibre entre plusieurs critères alors qu’elle se trouve dans une situation de supervision partielle et qu’une partie des critères échappent au calcul.

Le développement logiciel

On l’aura compris, le développement logiciel ne peut pas faire l’objet d’une supervision complète.

L’argument principal est que l’activité de développement n’est pas une suite d’actions répétables.

Ou plutôt que si un projet de développement est une suite d’actions répétables, cela signifie que les personnes ne tirent pas parti de la capacité de l’informatique à créer des outils pour gagner, au fur et à mesure, en efficacité.

Cela signifie que le pilotage par objectif est, sauf cas particulier, inadapté pour manager des équipes de développement.

Un projet informatique piloté par objectif et où le résultat est satisfaisant pourrait donc signifier deux choses : soit un grave problème de productivité, soit que les personnes biaisent les mesures et leur travail pour satisfaire les indicateurs.

La confiance & la mesure (sont sur un bateau)

Dans le management délégatif, la productivité dépend de l’autonomie laissée aux personnes pour qu’elles soient en capacité de faire les bons choix, et de leur confiance dans le management.

En effet, si les personnes n’ont pas confiance dans l’encadrement, elles dépenseront une partie de leur énergie à se protéger, par exemple en optimisant les métriques, plutôt qu’en faisant ce qui est le mieux pour l’organisation.

Selon l’auteur, chaque métrique sur le travail effectué remontée au management a un coût en terme de confiance. Il recommande donc — à l’inverse de certaines pratiques — de faire attention aux mesures qui sont remontées.

Il souligne notamment que, même si un manager ou une manageuse est de bonne volonté et n’essaie pas de se servir de chiffres à mauvais escient, cela n’est pas forcément le cas de la personne qui va le ou la remplacer. Les personnes ont donc raison de se méfier de toute remontée d’information qui pourrait se retourner contre elles, même à posteriori.

Si des mesures sont disponibles, il conseille de ne les fournir qu’aux personnes dont l’activité est mesurée pour qu’elles puissent améliorer leur propre travail, et de ne remonter au management que des résultats agrégés qui permettent de limiter les manipulations.

En conclusion

Le livre m’a fourni un cadre permettant d’expliquer des situations dont je n’avais qu’une compréhension partielle.

Le modèle qu’il propose est simple et convaincant, mais sa lecture est un peu déprimante, car il montre bien à quel point tout une partie du discours sur le management des projets informatiques correspond à des personnes qui préfèrent vivre dans l’illusion du contrôle plutôt que de changer leurs pratiques.

Quelques citations

Unlike mechanisms and organisms, organizations have subcomponents that realize they are being measured.

People working on activities that are being measured understand that dictating the uses of measurement is difficult and choose their behaviors accordingly. Unless trust between workers and managers is greater than usual in organizations, claims that measurement will only be used in a particular way are not credible. Regardless of official declarations, workers may believe it is in their interest to assume that available information will be used for performance evaluation and begin preparing for that possibility.

An effort dimension is critical when no valuable output can be created without devoting effort to the dimension.

The work of Holmström and Milgrom implies that the potential for dysfunction arises when any critical dimension of effort expenditure is not measured. The words of measurement experts and practitioners reveal varying degrees of understanding of the importance of measuring all critical dimensions of effort expenditure. Most experts recommend carefully choosing multiple measures that each represent different areas of performance. Some also recommend that chosen measures should be “balanced”, that they should not over-weight one aspect of performance in comparison with others. But most do not mention the importance, implied by the H-M model, of measuring without missing any critical dimension of performance.

Experts often suggest criteria for choosing areas to measure. Robert Lewis reports use of a single question at General Electric in the early Fifties as a test of whether performance in a particular area is key:

Will continued failure in this area prevent the attainment of management’s responsibility for advancing General Electric as a leader in a strong, competitive economy, even though results in all key areas are good?

A “yes” answer to the question meant that the area was key. Clearly, key areas represent critical dimensions of effort allocation according to the earlier stated definition. But deciding on key performance measures using the General Electric test does not, by itself, rule out dysfunction. Ruling out dysfunction requires that all key areas are identified. The system of measurement constructed by General Electric, then, could not be considered complete without a second question being answered in the affirmative, namely, “Have all key areas been identified?” The advice of many experts is incomplete in that it provides a means of recognizing key areas but fails to address the importance of not missing key areas. This shortcoming is serious because, as Holmström and Milgrom point out, measuring only easy-to-identify or easy-to-measure areas is a flawed practice. Nevertheless, there are many recognized measurement experts who expressly recommend practices that seem destined to lead to dysfunction. For example, Robert Grady and Deborah Caswell suggest a process that first identifies key areas and then pares down the set by ruling out areas that are difficult or expensive to measure.

What is a model? A model is a simplification; it is, by definition, a departure from reality. When reality is too complex to reason confidently about, it is often useful to extract details of a situation in the form of some simple assumptions, and then to see what can be concluded with confidence from this simpler view of the world. A model takes assumptions and converts them into corresponding conclusions. A modeling exercise is valuable, in part, because it structures reasoning and forces caution as we draw connections between assumptions and conclusions.

There are several temptations to be avoided when considering a model. One is to think that the slightest departure from a model assumption in a real situation negates the entire body of model conclusions. It is more appropriate to ask how sensitive a conclusion is to variation in a certain assumption. Often, assumptions have to be turned drastically on their heads to completely negate a model’s conclusions. And such dramatic turns are often much harder to believe in than the assumption that seemed so worrying at first. In examining models, then, one should maintain a healthy skepticism about assumptions but avoid throwing the baby out with the bath water.

Another temptation to avoid is making too literal an interpretation of a model or its components. Many models contain quantities that are intangible and cannot be measured in any definitive way. The model discussed later in this book is based on assumptions about people’s preferences for expending or conserving effort. Neither the preferences nor the effort are likely to be measurable in a real situation. But the model can still be useful. It is possible to agree or disagree with assumed relationships between such unmeasurable quantities (for example, do you agree or disagree that an employer’s satisfaction with a worker increases as the worker chooses to work harder?). Believable relationships between unmeasurable quantities can be transformed into conclusions about behaviors that can be observed and quantities that can be measured. So don’t let the fact that there is no such thing as an “effort meter” put you off of a model that makes assumptions about worker effort.

Perhaps the most common temptation people give in to when they encounter a model is to dismiss the model as being too simple to be a valid representation of real life. The model used in this book is simple. It is very simple at first and it becomes slightly less simple as we add factors that seem important. It is easy to complain that the model is too simple and that therefore it is not relevant to your particular situation. But it is less easy to say where in the transition from simple to complex the crucial differences arise. The special strength of modeling is in identifying these crucial differences. Models allow us to move from simple to complex in a structured way and thereby to see which added assumptions make little or no difference, and which ones turn day into night, or function into dysfunction.

The final test of the value of a model is whether it is useful or interesting to the person using it. Some valuable models are useful in a pragmatic, bottom-line sense—you can use their results to your immediate benefit. Others are useful or interesting in a broader sense, for the assistance they provide a reader who is striving to think about things in a new way. The R-H and H-M models summarized in the previous chapter succeed in the latter sense, in my view, despite the complaints I have lodged against them. They are provocative and also imperfect. I believe it is always more valuable to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of models than to attempt to rule them either valid or invalid, or realistic or unrealistic. It is in this spirit that I hope you will consider the model constructed in this book.

Eccles stresses the importance of “truly frank performance appraisals” and candid explanations of why some employees are rewarded more than others. Larkey and Caulkins provide convincing evidence that the required frankness and candor is rarely realized in actual practice and that, in fact, managers often do not provide the required correction because it is easier to defend ratings consistent with formal indicators of performance.

Empirical work on human motivation has shown that external motivators often crowd out internal motivation. This means that measurement-based management is in conflict with delegatory management. There is a negative interaction because of the implicit message of distrust that a measurement system conveys by the fact of its existence. The offer of an external reward for that which would otherwise be provided because of internal motivation may also have an insulting or debasing effect that lowers internal motivation.

Unfortunately, as customers come to expect products with more customized features and products become increasingly technologically advanced, a large and probably growing portion of important productive activity can be described as having high delegation and measurement costs. What courses of action are available to a principal in a situation that seems appropriate for neither measurement-based nor delegatory management? There are two options: She can convert the situation into one in which measurement is appropriate; or, she can convert the situation into one for which delegation is appropriate.

The first option is historically the most popular and manifests itself in the design of jobs and organizational structure. The traditional response to management difficulties is to redesign the job being done by the agent. There are several steps that can be taken to make jobs more susceptible to measurement, including:

Standardization. Almost all processes are repetitive at some level of abstraction. Although software development, for example, results in very different products that, as Frederick Brooks has noted, are not self-similar (similar segments of software are extracted into common modules or subroutines and so appear only once), the development can be said to proceed in a number of phases (for example, requirements definition, analysis, design, implementation, and maintenance). Where phases are extracted, standard methods of execution can be established. Measurements can be more easily made by noting variances from standards.

Specification. This step is closely related to standardization but deserves separate treatment because it implies something more detailed. Where standardization is the practice of deciding on appropriate product properties or worker behavior at a certain stage in a process, specification involves constructing a detailed model of the process. Measurement is made easier because variances from specification can be noted at any point in the process, not merely at points for which standards exist. Specification is, in effect, standardization of the entire process and every step in it. Leon Osterweil advocates an extreme version of standardization to manage the software development process in a paper titled “Software Processes Are Software Too.”

Subdivision, functional decomposition, and regrouping. Costs of measuring jobs that are composed of diverse and specialized activities can sometimes be reduced by dividing the job into tasks and subtasks, and grouping similar tasks and subtasks. There are several advantages to this approach. First, grouping similar activities makes repetition and self-similarity more visible within the complexity of the overall process. Second, people working on similar activities can be assigned overseers that have the same specialized knowledge as workers; accountants work for accountants, engineers for engineers, and so on. Third, if subdivision is successful, then standardization and specification can be facilitated by isolating similar aspects of jobs.

Not all development or production processes lend themselves to easy conversion to measurement appropriateness. As has been mentioned in discussing choice of supervisory mode (full, partial, or none), the degree to which measurement costs can be decreased depends not only on the ingenuity of measurers and job redesigners (for example, the principal), but also on the inherent nature of the job or task. As was noted, despite Osterweil’s optimism about prospects for programming software development, some experts question the feasibility and wisdom of extensive subdivision, specification, and standardization of software development. Curtis et al. and M.M. Lehman submit that human processes may be too dynamic to be captured by static representations. DeMarco went even further in questioning the commonly expressed desire to render software development rotable—that is, to make the process repeatable in the sense that next steps are specified for any eventuality and such that it can be executed by rote (see Humphrey on the virtues of repeatability in software development). DeMarco’s comments relate specifically to software development but are applicable to other development and production processes:

The idea of a software factory is a joke — that we can build software by rote — that’s ridiculous. If the work is deterministic, we will do with it what we do with any other big piece of deterministic work. We’ll put the deterministic work inside the computer and let the computer do the deterministic portion, leaving the person who interacts with the computer—the other half of the system—to do the work whose roteness has decreased, not increased. Every time you automate something, what’s left of the person’s work is less deterministic, until eventually, when you automate enough, there’s no deterministic element left for the person’s work—no rote. We’ve driven rote out of the system… Little by little, the work is becoming zero-percent rotable… Our work is not deterministic. It’s far too inventive. We’re knowledge workers, not factory workers.

DeMarco argues that there are certain jobs and certain aspects of jobs that resist redesign by subdivision, specification, and standardization. Ishikawa lists similar redesign limitations. Such

More specifically, the principal can try to convince the agent that his prospects for future rewards are not at all dependent on the measurements. But, as March and Simon observe, workers in real organizations are notoriously cynical about declarations to this effect. They know that the rate at which widgets, interviews, or lines of code are produced does matter. All else being equal, faster production is preferable to slower production. Workers expect, then, that rewards will go to the speedy. Denying the obvious is unlikely to be of help to the principal.

When the benefits associated with the direction of a particular measure are obvious (such as high quantity or low defect rates), agents become sensitive to a competitive dynamic that is not represented in models that feature one principal and one agent. As agents become familiar with the system of measurement and discover ways to exploit it, they realize that their coworkers are also discovering the means of exploitation. A dilemma arises. If coworkers do not exploit the system, then a given worker will benefit from exploiting the system because he will look better by measured criteria than his more honest coworkers. If coworkers do exploit the system, the given worker will still benefit from exploiting the system since he will not seem to lag behind his less honest coworkers. This logic applies to all workers in the group. Exploiting the system is, then, a dominating strategy for all workers.

Paulish conceded that it is impossible to control what managers do with measurement information once they have it; and that managers may be tempted to do secretly other than what was agreed on or admitted publicly. As long as possibilities like these loom in workers' minds, the incentive to exploit a measurement system remains.

Quiet non-compliance is worse than the more visible variety because the former conveys the impression to managers that they are seeing things as they really are. The quiet subversion of a measurement system can also be worse than no system of measurement at all. With no system, managers do not know what is happening, and they know that they do not know. With a quietly subverted system, managers still do not know what is happening, but they think they do. They make decisions, therefore, about process improvements and the like based on faulty information. Ironically, this sort of measurement has the opposite of its intended effect. Introduced to provide a clearer picture of what is happening in the organization, it instead creates layers of subterfuge and intrigue that vastly complicate learning about the organization. Long-term damage is done; by creating a situation in which workers feel compelled to resort to deception (whether overt or in the less sinister form of, say, unwarranted optimism), measurement designers have driven a wedge between managers and workers. With the wedge in place, measurers must doubt the accuracy of all future information coming from workers.

In real settings, principals are charged with controlling activity in their areas of organizational responsibility. Unfortunately, the need for control is often interpreted narrowly as a need for measurement-based control. The principal’s job is then usually perceived to be the redesign of agent tasks to make them more measurable. The inclination to interpret control narrowly is due to what might be called a standardization reflex.

Since the latter part of the nineteenth century, institutions of governance have taken on a very similar form, which is hierarchical and functionally organized. There are a variety of explanations for this (see, for example, Chandler; Williamson), but one factor almost always mentioned is that this organizational form seems particularly appropriate for achieving job standardization, specification, and subdivision as described in Chapter Twelve. Huge productivity gains have resulted. A reflexive tendency toward standardizing, specifying, subdividing, and measuring that evolved from refining mass production processes is apparent in today’s organizations, and in many circumstances it is still profitable.

The standardization reflex is obviously aimed at converting tasks to make them more measurement-appropriate. Given historical precedent, modern principals can hardly be faulted for assuming that conversion for measurement is the job that they have been commissioned to do. In terms of this book’s model, the principal believes she is charged with the redesign of agent tasks so that measurement costs are lowered and full supervision can be gainfully realized. As has been shown, however, the standardization reflex does not always serve organizations well. The value added to some products by customization of its components is appreciable. Redesigns for measurement tend to fail when the setting and product are not particularly suited to measurement. A situation that results from a failed attempt at conversion would still require partial supervision. It is at this point that casual observation might be invoked to reveal that full supervision has not been realized.

A principal might react to a failed control system by constructing another very similar system simply because she cannot imagine, and does not experience, the benefits of a significantly different alternative, such as delegatory management. Managing a measurement-based control system provides no experience relevant to alternative systems. A principal who learns experimentally will not gather data needed to compare delegatory and measurement-based alternatives, if she is not inclined to try the former. A principal is more likely to believe in the effectiveness of small changes in what she has been doing than in the effectiveness of large changes, especially since the latter will seem more risky.

Computer software development is an intriguing case for two reasons. First, interest in measurement is high among software practitioners, so the issues raised here are relevant to practice. Second, the model developed here suggests that software development is usually poorly suited to measurement-based control.

Consultants, who are not a part of an organization and thus do not identify with it and who stand to benefit greatly from guile and convenient beliefs, are ready prey to dysfunctional pressures.

The fundamental message of this book is that organizational measurement is hard. The organizational landscape is littered with the twisted wrecks of measurement systems designed by people who thought measurement was simple. If you catch yourself thinking things like, “Establishing a successful measurement program is easy if you just choose your measures carefully,” watch out! History has shown otherwise. I urge you to regard all such statements as skeptically as you might regard the statement “that pistol is not loaded.”

The first step to solving the measurement problem is facing its true difficulties. If you feel frustration, push past it and formulate a plan for dealing with the difficulties. Successful plans may have what seem like extreme elements. For example, it might be necessary to enforce very strict requirements on the acceptable use of measurement. Managers might need to satisfy themselves with less access to data than they want, to preserve the validity of the data they are permitted to see. Most of all, organizational leaders will have to work twice as hard as they might like to establish a culture conducive to measurement, in which measurement is seen as a useful way to learn but not as the be-all and end-all of performance management.

A good test of whether you are succeeding in creating the right kind of culture is to ask yourself what seems to be driving the people around you to do a good job. Is the motivation of workers primarily internal or external? That is, are people in your organization driven primarily by feelings of identification with the organization and their fellow team members? Do they work hard because they don’t want to let their coworkers down? Or, are they driven mostly by a desire to do well on their next performance review and get a big raise? Strive for the former, but be prepared that, too often, measurement systems produce the latter.

The difference between these two types of motivation is important because of what is perhaps the most basic problem of organized activity. In a typical organization, an individual worker confronts tens or hundreds of small decisions every day. In making each decision, he can choose to do what is best for the organization or he can choose what is best for himself. As I have written repeatedly, what is best for the organization almost never is exactly the same as what is best for the worker’s measurement performance. So, if the worker feels that the measurement system is of greatest importance, then each of his decisions will be at least a little worse than it might have been if he had felt compelled to choose what is best for the organization. Add this effect across many workers and the result is significant. Often, it is the difference between transitory and lasting success for the organization. An organization can try to keep its measurement systems and other formal criteria aligned with its overall goals, but this is a difficult and expensive process at best.

The good news is that you can succeed in producing a culture conducive to measurement. There are organizations in which people seem to have given themselves completely to the pursuit of organizational goals, at least temporarily, organizations in which members hunger for measurement as a tool that helps get the job done. In these settings, there is nothing special about measurement; measurement seems neither remarkable nor threatening. To use measurement inappropriately would betray a sacred trust, and no one would consider such a betrayal.